West African College of Physicians (Nigeria Chapter)

Healthcare governance, Health insurance and the hidden epidemic: Time to confront the scourge of STDs.

Dr. Rasheed Ajani Bakare

FWACP (Laboratory Medicine)

The 16th Sir Samuel Manuwa Lecture

43rd Annual General & Scientific Meeting (AGSM)

ABEOKUTA, NIGERIA

July 2019

© 2019 West African College Of Physicians (Nigeria Chapter)

Printed 2019

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the West African College of Physicians -Nigerian Chapter who is the copyright holder.

Published by the

West African College of Physicians (Nigeria Chapter)

6, TAYLOR DRIVE, OFF EDMUND CRESCENT, MEDICAL COMPOUND. P.M.B. 2023, YABA - LAGOS, NIGERIA

Tel: 08176673530-2, 08176673540.

e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]

website: www.wac-physicians.org

Printed in Lagos by

Osprints Glory Ventures

Tel.: 08023336851, 08062647637

Chief The Hon. Sir Samuel Manuwa

CMG, OBE, C St J

MD, FRCS, FRCP, FACS, FACP, FICS, FWACS, FWACP, FNMC, FRSA, FRS (Ed). Hon LLD (Edin), Hon D.SC (Nig.), Hon D.SC (Ibadan), Hon D. Litt (Ife). 1st Inspector-General of Medical Services & Chief Medical Adviser to the Federal Government of Nigeria

Prof. Rasheed Ajani Bakare FWACP (Laboratory Medicine)

(The Author)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Picture of Sir Dr. Samuel Manuwa iii

Picture of Prof. Rasheed Ajani Bakare ` iv

Table of contents v

Lecture notes 1

References 56

Acknowledgment 58

Biography of Prof. Rasheed Ajani Bakare 64

PROTOCOLS

Introduction

I feel highly honoured to stand before you today to deliver the 16thin the series of Sir Samuel Manuwa lecture on behalf of Faculty of Laboratory medicine. This is the 3rd lecture from the faculty of Laboratory Medicine and I want to thank my Faculty for the kind nomination. I also wish to thank the leadership of the Nigerian chapter of the West African College of Physicians for accepting my Faculty’s nomination.

This is to specially appreciate the efforts of my Faculty chairman, Dr. Tony Onipede, who used everything at his disposal to “force” me to accept the nomination by the Faculty to give the lecture. Again, by sheer coincidence, the lecture was scheduled to hold in my town of ancestral origin; Abeokuta the heart of Egbaland. As I was born and bred in Abeokuta, it is apt to state that: “Abeokuta is where my story begins” Egba people are renowned for their Pride, honor, dignity, integrity, fashion, radicalism, civilization, patriotism, hardworking nature and respect. “We are warriors who love peace!!” God Bless Abeokuta, the land filled with milk and honey. Indeed, i am proud to hail from Egbaland.

I have a proud heritage in Abeokuta Grammar School, Abeokuta, my Alma Mater. My association with Abeokuta Grammar School started in 1967 when I took the common entrance examination to the School. Luckily for me, I passed and was offered admission which I readily accepted. Incidentally, I was fortunate to be part of the Diamond Jubilee celebrations and I recall those good old days with a lot of nostalgia. I had earlier attended Egba Junior comprehensive high school where I chose commercial subjects over Science subjects, the sound of typewriters was a major attraction to me and I often fantasized on becoming a renowned typist someday. Fortunately, I dropped out of the school in the first term. I secured two different admission offers to the University of Ibadan in 1975, firstly a direct entry to study Pharmacology and the other into 100 levels to study Medicine. I chose to study Medicine against the advice of friends and relations who thought Medicine was a very difficult subject at the University of Ibadan. I should have been a Copy typist or “non confidential” Secretary if I decided to complete my secondary education at Egba High School or a Pharmacologist if opted for direct admission with my A-level results. Either way, I would have had no opportunity to stand before you today to give this lecture. To God be the Glory! I consider it noteworthy that, similarly, Oloye Sir Samuel Olayinka Ayodeji Manuwa CMG, OBE rose from humble roots as the son of Reverend Benjamin Manuwa, a clergyman from Itebu waterside in present day Ondo state.

Sir Samuel Manuwa, physician, surgeon, medical and university administrator and elder statesman, was born at Porogun, Ijebu-Ode on 4th of March, 1903. He was the elder son of Rev. Benjamin Ilowo Manuwa and grandson of Oba Alaiyeluwa Kuehin Elero of Itebu Manuwa, he lost his mother at the tender age of four, an event which was to generate ultimate self-reliance. He received his early education at Aiyesan in Okitipupa Division, the CMS Grammar School and King’s College, Lagos where he began to lay the foundations for prodigious hard work and industry. Memories of his school days are replete with anecdotes-the intimidating story is told of how at King’s, this austere, disciplined and punctilious boy constantly kept a sharpened pencil, a measuring rule and India rubber in his breast pocket, and could never be persuaded to lend these items even to his closest associates for fear of losing them permanently!

Samuel Manuwa left King’s College with the best results in the Higher Matriculation in his class, taught at the Grammar School for a year before departing for Britain in 1920. His record in Edinburgh University bristles with scholarship. He won the Robert Wilson Memorial Prize and Medal in Chemistry, the keenly sought Wellcome Prize and Medal in Medicine and earned a Demonstratorship in Human Anatomy. Qualifying MB ChB in 1926, he returned home the following year to join the Colonial Medical Service. Within a year of his return he had gathered material for and written a classic treatise on Chronic Splenomegaly in West Africa which was to earn him the MD(Edin) in 1934. Dr. Manuwa`s demonstrated academic and professional competence ensured his rapid rise through the ranks, from Medical Officer to Senior Surgical Specialist, acquiring en passant an “Excision knife for Tropical Ulcers”. Everywhere he went his expertise was undisputed and his name soon became a household word.

From official records, we glean that at Adeoyo hospital, Ibadan, Dr. Manuwa had done wonders! This small hospital with only 120 beds was noted throughout Nigeria as the best-run hospital in the country. He virtually stamped out corruption and the whole atmosphere was a vast improvement on anything available in Lagos. His superbly agile and efficient mind was always at the cutting edge of medical advance and he would often unwittingly embarrass his academic colleagues by quoting a paper from the previous Friday’s Lancet.

His contributions to education in general have been acknowledged by Nigerian Universities-Nsukka, Ife and notably my alma-mata, Ibadan with which his connection dates back to the birth of that University. I shall at this point digress a bit more on the role Sir Manuwa played in positive transformation of my alma-mata and domicile of practice, University College Hospital Ibadan. He was one of its earliest Honorary Associates, went to receive its D. Schonoris causa, and subsequently adorned the Pro-Chancellorship and Chairmanship of Council for nine years. He inspired the formation of the West African Inter-University Games and donated two gold championship cups. His colleagues in the Nigeria Medical Service marked his contributions to medical education by donating the annual award-the Sir Samuel Manuwa gold medal for the best graduate in Medicine at the University of Ibadan. Dr Kenneth Mellanby, first Principal of University College Ibadan had this much to say at the time:

“Perhaps Sir Samuel’s most significant contribution was that he was, as Inspector General of Medical Services, largely responsible for persuading the Federal Government to abandon its former plans to use the old cottage-type Army Hospital at Eleiyele as the University Teaching Hospital, and to build instead a completely new and modern hospital at Hammock Road (now Queen Elizabeth Road) which is now the pride of Tropical Africa.”

The major forte in the last decade of his life was unquestionably consummate absorption in the Federal Public Service Commission and in University affairs. As Chairman of Council, University of Ibadan, he always betrayed a dignified presence, a large hinterland of administrative and procedural expertise, of learning and culture, a profound respect for tradition, a clear consideration for the other man’s point of view, objectivity, fair-mindedness and an authority that compelled attention. Differences of opinion were always amicably disposed, and above all, his outwardly gubernatorial posture concealed a deep inner warmth, tenderness, and love for his fellow being.

Indeed, Chief, the honourable sir Samuel Layinka Ayodeji Manuwa, the Iyasere of Itebu-Manuwa, the Obadugba of Ondo, the Olowa Luwagboye of Ijebu-Ode CMG, OBE, C St J MD FRCS FRCP FACS FACP FICS FWACS FWACP FMCS FRSA FRS (Edin) Hon LLD (Edin) Hon D.SC (Nig.) Hon D.SC (Ibadan) Hon.D.Litt (Ife) was an enigma and a gentleman extraordinarie, larger still in death as his good deeds live on.

A legend in his own life-time, medical titan in his generation, international medical icon for all time, may Sir Samuel Manuwa continue to rest in perfect peace, Amen.

The theme of this year’s AGSM is Healthcare Governance in Nigeria with

Sub-themes "The State of Health Insurance and Healthcare Financing in Nigeria, I have therefore decided to speak on: Healthcare governance, Health insurance and the hidden epidemic: Time to confront the scourge of STDs.

1.0 Background (Definitions and Brief History)

Healthcare governance is a general term for the overall framework through which organizations are accountable for continuously improving clinical, corporate, staff, and financial performance.

Good governance is an indeterminate term used in the international development literature to describe how public institutions conduct public affairs and manage public resources. It is "the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented)".

Although Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) are as old as mankind, perceptions have changed over time and have been linked to punishments for the sin of blasphemy, consequences of poor sanitation/hygiene and subsequently reported as "new plague" imported to Europe rapidly spread by soldiers in the late 15th and 16th century. With the developments in science and technology in the late 19th and beginning of 20th century, this hidden epidemic (STDs)came to be realized as a potential threat to millions of "normal" and "famous" people and regarded as an important public health concern. (1)

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) have recently been used interchangeably to replace Venereal Diseases (VD) which is an older terminology that has become obsolete and rarely used. Although “Venereologist” is still being used for clinicians who specialize in STDs/STIs, Genitourinary Medicine has virtually replaced that terminology in many other countries. Sexually Transmissible Infections on the other hand denotes the potential of being sexually transmitted. The use of STIs has become more favoured on the premise that some of the infections could be asymptomatic and not qualified to be diseases. However, taking into cognizance many other parameters including the pros and cons of both STDs and STIs, a newly proposed terminology is STID (Sexually Transmissible Infectious Disease). This term conveniently and unambiguously accommodates other diseases such as; Vaginal candidiasis, Bacterial Vaginosis, Congenital Syphilis and many others that cannot be classified clearly. (2)

Venereology and Dermatology have co-existed and are occasionally regarded as a single unit in some countries. A common history that is based on convenience, interest and expertise formed the basis for this association both in Nigeria and other countries.

A broader concept not limited to only STIs is sexual health which is a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality and not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled. (3)

STDs are behavior-linked diseases that result from unprotected sex. Behavioral, biological, and social factors, all contribute to the likelihood of contracting a STD. Microenvironments, including microbiological, hormonal, and immunologic factors, influence individual susceptibility and transmission potential for STDs. These microenvironments are partially determined by an individual's sexual practices, substance use, and other health behaviors. These health behaviors, in turn, are influenced by socioeconomic, epidemiologic, and other macro environmental factors.

STI clinics in Nigeria formally started in the 1960s with the commencement of specialist care to patients, initially in a single room at the department of Medical Microbiology, University College Hospital (UCH) Ibadan. Subsequent expansion as a multidisciplinary clinic in the early 1970s has led to the establishment of the Special Treatment Clinic (STC) at UCH, a WHO certified centre for management of STIs. At present, a number of hospitals in Nigeria also provide services as either STI clinics under the Medical Microbiology or as multidisciplinary clinics involving departments/units such as Dermatology, Community Medicine and Obstetrics & Gynaecology. Globally clinics offering such services have been named differentially as sexual health clinics with increasing patronage at different levels. (4)

The scourge of STDs has continued to significantly impact on economies even in developed countries. In the United States, treatment of STIs, including HIV infection, cost nearly $16 billion annually.(5) The global burden of morbidity and mortality due to STDs has continued to be a hindrance to good quality of life in addition to its deleterious effect on sexual/reproductive health in adults and newborn/child health. The economic burden of STDs on both individual and national health systems especially in middle and low-income countries, presents a clear need for concerted efforts at all levels to confront the menace.

2.0 Epidemiology of STIs: The hidden epidemic

Globally, about a million people become infected with STIs every day. Over 357 million new cases of bacterial/protozoal infections including: Trichomonas vaginalis (142 million) Chlamydia trachomatis (131 million), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (78 million) and syphilis (6 million), occur annually. sub-Saharan Africa is the second worst hit and bears approximately 40% of the global burden of STIs. (6)In the UK, the prevalence of STIs have fluctuated in the last 100 years based on social, economic and technological trends. Gonorrhoea, Syphilis, Chlamydia, HPV/Genital warts and HIV/AIDs have remained relevant throughout history. (7) Viral STIs have equally maintained very high prevalence with herpes simplex type 2 accounting for an estimated 417 million infections, while about 291 million women are infected with human papillomavirus. (8) Variations exist in these prevalence rates based on region and gender of the population concerned but complications are disproportionately worse among females in most instances.

The advent of HIV/AIDs has overwhelmingly altered the trend of STIs, with consequent re-emergence, acquisition and progression of almost all the conventional STIs especially among the MSM.(9) Conversely, the persons infected with other STIs such as Syphilis, Chancroid ulcers or genital herpes simplex virus are greatly at increased risk of acquisition or transmission of HIV.(9)Among pregnant women, untreated early syphilis could lead to stillbirth (25%) and neonatal deaths (14%) with an overall perinatal mortality of about 40%.(9) Annually, about 4000 neonates lose their sights as result of untreated maternal gonococcal and chlamydial infection of the eyes.(9) Cervical cancer which occurs as a result of infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) is associated with death of about 240 000 women annually in resource-poor nations.(9)Infertility which is of global public health concern is associated with STIs like gonorrhoea and chlamydia.

In Nigeria, STIs continue to constitute significant medical, social and economic problems among both rural and urban dwellers with historic higher prevalence in different parts of the country. (10)

In terms of age adolescents and young adults are at higher risk of contracting STI. Existing prevalence figures in Nigeria do not differ significantly from global figures. Community-based surveys of adolescents (14-19 years) in Nigeria recorded the following prevalence rates:T. vaginalis (9 – 11%), N. gonorrhea (0 – 3%), C. trachomatis (2 – 11%). In developing countries about one half of the population is less than 15 years of age. This age group, 15-24 years which has the highest STI prevalence, is entering the period of sexual activity, resulting in higher incidence of STI cases.

It is really unfortunate that poverty and gender inequalities have forced some women to turn to commercial sex as a means of survival. Older men, on the other hand, tend to be more sexually adventurous and are more likely to have disposable income therefore enhancing the economic success of the female sex workers. Also, cultural practices (i.e. abstinence by pregnant female partners) tend to encourage multiple sexual partnerships in males:

Certain occupations tend to reinforce high-risk sexual behavior. These are; the mobile workers (long distance drivers, professionals, Migrant workers (oil workers) and the Sex workers. Urbanization and migrant labour favours transmission of STI by increasing demand for commercial sex.

Recent data however seem to show no significant variation in the prevalence of STI in rural and urban areas.

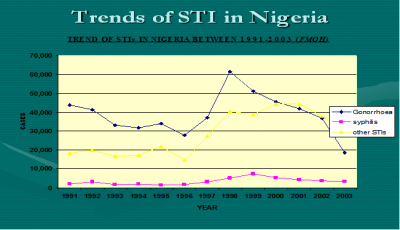

Figure 1: Trends of STIs in Nigeria (1991-2003)

Figure 2: Patterns of STIs seen among patients attending the STC, University College Hospital, Ibadan. C (Herpertic Labia ulcers) and D (Genital warts).

2.1 Factors that Contribute to the Hidden Epidemic

Biological factors that affect the risk of acquiring or transmitting STDs include gender and other preexisting or concurrent STDs including HIV infection. Other contributory biological factors include the lack of conspicuous signs and symptoms manifested by infected persons, the long lag time from initial infection to signs of severe complications, and the propensity of STDs to more easily infect young women and female adolescents than men. Additionally, the potential impact of male circumcision, vaginal douching, risky sexual practices, and other factors on the spread of STDs cannot be overemphasized.

Asymptomatic Infections

Several STDs either do not produce acute symptoms or clinical signs of disease or do not produce symptoms sufficiently severe for an infected individual to seek medical attention. About 85 percent of women with Chlamydial infection are asymptomatic. (11) Asymptomatic infection also contributes to the spread of viral STDs including HIV infection, hepatitis B virus infection, genital herpes, and human papillomavirus infection. HIV infection is a prime example of how certain STDs that may go unrecognized for many years allow wide dissemination of infection before it is detected and treated. Lack of awareness that most cases of certain STDs are asymptomatic or otherwise unrecognized leads many susceptible persons to falsely believe that it is possible to tell whether a potential partner is infected with an STD, and similarly explains why many infected asymptomatic persons fail to take precautions to avoid transmitting their infection. Even when symptoms are present, many STDs have nonspecific signs and symptoms, making them difficult to diagnose without laboratory tests. Asymptomatic infection, therefore, is an extremely important biological factor that reduces the likelihood that infected individuals will seek health care and/or receive appropriate diagnoses. This hinders detection and treatment of the infection, increases the period of infectiousness, and thereby promotes the spread of the infection.

Lag Time to Complications

Another biological factor that contributes to the STD epidemic is the long period of time (sometimes years or decades) from initial infection until the appearance of clinically significant problems. The best examples of sexually transmitted pathogens and complications that have long lag times are (a) human papillomavirus and cervical cancer and (b) hepatitis B virus and liver cancer. In both instances, the initial phase of the infection is often asymptomatic and creates obstacles to detection and treatment. In addition, the clinical signs of the associated life-threatening cancers usually do not appear until years or decades after the initial infection. Because of this phenomenon, many cases of STD-related cancers and other long-term complications are not attributed to a sexually transmitted infection. At both individual and population levels, the lack of a perceived connection between sexually transmitted infections and these serious complications reduces both the perceived significance of STDs and the motivation to undertake preventive action. Although the lag time between exposure to HIV and development of clinical symptoms of AIDS likewise can be quite long, there is greater awareness of the link between unprotected sex and the risk of acquiring HIV, and ultimately AIDS, compared to other STDs.

Increased Susceptibility of Women and Female Adolescents

Age and gender may influence risk for an STD. Specifically, young women and female adolescents are more susceptible to STDs compared to their male counterparts because of the biological characteristics of their anatomy (12). This is because in puberty and young adulthood, specific cells (columnar epithelium) that are especially sensitive to invasion by certain sexually transmitted organisms, such as chlamydial and gonococcus, extend from the inner cervix out over the vaginal surface of the cervix, where they are unprotected by cervical mucus. These cells eventually recede into the inner cervix with age.

In addition to biological factors, women and female adolescents may also find it more difficult than men to implement protective behaviors, partly because of the power imbalance between men and women. For example, condoms are the most effective protection against STDs for sexually active persons, but the decision whether to use a condom is ultimately up to the male partner, and negotiating condom use may be difficult for women.

Other biological factors

Other biological factors that may increase risk for acquiring, transmitting, or developing complications of certain STDs include presence of male penile foreskin, vaginal douching, risky sexual practices, use of hormonal contraceptives or intrauterine contraceptive devices, cervical ectopy, immunity resulting from prior sexually transmitted or related infections, and nonspecific immunity conferred by normal vaginal flora.

Lack of male circumcision seems to increase the risk of acquiring and perhaps transmitting certain STDs. A review of 30 published epidemiological studies that examined the relationship between HIV infection and male circumcision concluded that most studies found a statistically significant association between lack of circumcision and increased risk for HIV infection (13). Another study of gay men suggested that uncircumcised men were twice as likely to be infected with HIV compared to circumcised men (14). As a result of these studies, some have proposed that male circumcision be considered an intervention to prevent HIV infection. Several studies have found associations between lack of circumcision and other STDs, including chancroid (15). It has thus been hypothesized that lack of circumcision increases risk for STDs because (a) the cells that line the fold of skin that is removed by circumcision are prone to trauma or infection, (b) this fold of skin may serve as a reservoir for pathogens, and (c) this fold of skin may increase the likelihood that infections will go undetected (15).

Vaginal douching seems to increase risk for pelvic inflammatory disease. In one study, compared to women who did not douche, women who douched during the previous 3-month period were twice as likely to have clinical pelvic inflammatory disease (16). The risk for pelvic inflammatory disease seems to increase with greater frequency of douching (16, 17).

Certain sexual practices such as receptive rectal intercourse predispose to STDs. As earlier mentioned, STDs such as HIV infection and hepatitis B virus infection are more easily acquired by rectal intercourse than by vaginal intercourse. This may be because the bleeding and tissue trauma that can result from rectal intercourse facilitate invasion by pathogens. Other sexual practices, such as sex during menses and "dry sex," also predispose to acquisition of STDs.

The influence of hormonal contraceptives on acquisition and transmission of STDs is not fully defined. However, several studies have found oral contraceptive use to be associated with increased risk of acquiring chlamydial infection (18) but with decreased risk of developing pelvic inflammatory disease among women with chlamydial infection (17, 19). A recent study in Kenya has demonstrated that use of oral contraceptives or injectable progesterone among women with HIV-1 infection is associated with increased shedding of HIV-1 DNA from the cervix (20).

Cervical ectopy (extension of columnar epithelial cells present in the adult endocervix onto the exposed portion of the cervix within the vagina) has also been found to be a risk factor for HIV infection. Among women attending an STD clinic and among college women, cervical ectopy was positively associated with use of oral contraceptives and with chlamydial infection; ectopy disappeared with increasing age.

Cross-immunity (protection conferred by prior infection with a different pathogen) also occurs. For example, a prospective study of women found that asymptomatic shedding of herpes simplex virus type 2 occurs more often during the first three months after acquisition of primary type 2 disease (21). Among persons with herpes simplex virus type 2 infections, previous infection with type 1 virus was associated with a lower rate of asymptomatic viral shedding. This observation suggests that, as prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 infections in childhood decline, the risk of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection may be increased when this STD is encountered by a sexually active adult. Nonspecific immunity may make some individuals more resistant to certain STDs even though they have never experienced prior STDs or related infections.

Social factors

On a population level, preventing the spread of STDs is difficult without addressing social issues that have a tremendous influence on transmission of STDs. Some fundamental societal problems such as poverty, lack of education, and social inequity indirectly increase the prevalence of STDs in certain populations. In addition, lack of openness and mixed messages regarding sexuality create obstacles to STD prevention for the entire population and contribute to the hidden nature of the STDs. In the following discussion, I hereby highlight several social problems that directly affect the spread of STDs in subpopulations and shows how societal norms regarding sexuality impede prevention of STDs.

Poverty and Inadequate Access to Health Care

Health insurance coverage enables individuals to obtain professional assistance in order to prevent potential exposures to sexually transmitted infections and to seek care for suspected STDs. Uninsured persons delay seeking care for health problems longer than those who have private insurance or Medicaid coverage (23). Those with private health insurance who are living at or near poverty level have limited access to health care because of copayments and deductibles that are typically part of private insurance coverage (24). Private health insurance generally provides the most comprehensive coverage with the greatest access to physicians and other health care professionals. However, not all plans offer adequate coverage for STD-related services. Little information is available on coverage for STD-related services in the private health care sector.

The age and ethnic groups with the highest rates of STDs are also the groups with the poorest access to health services. One-third of persons in high-risk age groups are uninsured or covered by Medicaid (25). Even in developed climes, Hispanic and African Americans are the most likely to lack insurance coverage.

Substance Use

Substance use, especially drugs and alcohol, is associated with STDs at both population and individual levels. At the population level, rates of STDs are high in geographic areas where rates of substance use are also high, and rates of substance use and STDs have also been shown to co-vary temporally (26). At the individual level, persons who use substances are more likely to acquire STDs. There are several possible reasons for this association. One is that underlying social and individual factors lead both to higher rates of STDs and to greater use of substances. Social factors such as poverty, lack of economic and educational opportunities, and weak community infrastructure may contribute to both outcomes. Individual factors, such as risk-taking and low self-efficacy, could similarly contribute to both outcomes. Use of substances may also directly contribute to risk of STD infection by undermining an individual's cognitive and social skills, thus making it more difficult to take actions needed to protect themselves against STDs. For example, at low doses cocaine can decrease inhibitions and heighten sexuality, leading to increased numbers of sexual encounters and partners and to increased high-risk sexual behaviors (27). In addition, drug users may be at greater risk for STDs as a result of the practice of trading sex for drugs; in these situations, drug users have a large number of high-risk partners (27). Those who are involved in frequent and sustained use of substances are most likely to be at risk for STDs.

Sexual Abuse and Violence

Sexual violence against women and sexual abuse of children are societal problems of enormous consequences. Approximately 500,000 women were raped annually in 1992 and 1993 in the United States (28), and studies suggest that approximately one in three young girls and one in six young boys may experience at least one sexually abusive episode by the time they reach adulthood (29). Women who have been sexually abused during childhood are twice as likely to have gynecological problems, including STDs, compared to women who do not have such a history. In addition, women with a history of involuntary sexual intercourse are more likely to have voluntary intercourse at an earlier age (a risk factor for STDs) and to have subsequent psychological problems (30).

Transmission of STDs as the result of sexual abuse is particularly salient among prepubescent children and very young adolescents. STDs among children presenting for care after the neonatal period almost always indicate sexual abuse (31-33). Sexually abused children may have severe and long-lasting psychological consequences, may become sexual abusers themselves, and may abuse children. In addition, they may engage in a pattern of high-risk behavior that often puts them at risk for further abuse and subsequent STDs. Guidelines for the clinical management of children with STDs as a result of suspected abuse have been published (31-33).

Many women who are subjected to sexual violence may not be able to implement practices to protect against STDs or pregnancy. A phenomenon that also may impede protective behaviors among women is the pairing of older men with young women. The age discrepancy between older men and younger, sometimes adolescent, females may predispose to power imbalances in the relationship, thus increasing the potential for involuntary intercourse, lack of protective behavior, and exposure to STDs. In addition, early initiation of sexual intercourse among adolescent males with an older female partner has been shown to increase the number of sex partners later in life.

STDs Among Vulnerable Populations

STDs, like most communicable diseases in the United States, disproportionately affect Vulnerable groups and persons who are in social networks where high-risk health behaviors are common. These groups are often of low priority to policymakers since they possess little political power or influence and, without publicly sponsored health services, would not have access to STD-related services. In addition, these groups are difficult to reach, difficult to teach, and difficult to treat (34). However, they are important from an STD prevention perspective because they represent "core" transmitters of STDs in the population (35). Populations at high risk for STDs that require special attention include: sex workers including MSM, homeless persons, internally displaced persons and adolescents in detention.

Sex workers and their clients represent traditional "core" transmitters of STDs (36). Extremely high rates of STDs, including HIV infection, have been reported among sex workers in the United States (37). For example, in a national study of more than 1,300 female sex workers, 56 percent had serological evidence of past or current hepatitis B virus infection. (38). Studies in the late 1970s and early 1980s found that up to 22 percent of sex workers screened in some U.S. cities were infected with gonorrhea. (36).

My Colleagues and I conducted a study to determine the pattern of STDs among commercial sex workers (CSWs) in Ibadan, Nigeria. The subjects were 169 CSWs randomly selected from 18 brothels, majority of who were examined and investigated in their rooms. Another 136 women without symptoms who visited the special treatment clinic, University College Hospital, Ibadan were selected as a normal control group. Vaginal candidiasis was the most common STD diagnosed in both CSWs and the control group. The other STDs in their order of frequency were HIV infection 34.3%, Bacterial vaginosis 24.9%, trichomoniasis 21.9% gonorrhoea and “genital ulcers” had an incidence of 16.6% each. Other important conditions were tinea cruris 18.9%, scabies 7.7% genital warts 6.5% and 4.1% of them had syphilis sero-positivity. All the 13 CSWs that had scabies, 4(36.4%) with genital warts and 19(67.9%) with “genital ulcers” also had HIV infection. While there was no significant difference between the CSWs with vaginal candidiasis, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and the control group, the HIV positivity was significantly higher (P<0.001) in CSWs than in the control subjects. These findings suggest that women who exchange sexual services for money can no longer be ignored, and should therefore be identified and made to participate in STD prevention and control programmes. (39-43)

As mentioned previously, exchanging sex for drugs is a major factor in the recent upsurge in syphilis infections in several large cities. In addition to unprotected sex with multiple partners, female sex workers also are likely to have other factors that increase their risk for STDs, such as intravenous drug use, a history of being victims of sexual abuse and violence, and inadequate access to health care.

In Nigeria, there are no policies related to sex workers unlike in the United States, where policies have ranged from punitive interventions such as criminalizing prostitution, to legalizing and controlling it, as is the case in many European countries.

Runaways and homeless adolescents are at increased risk for STDs because they tend to be more sexually active than other adolescents; have multiple high-risk sexual behaviors that include trading sex for drugs or money; have high levels of substance; and are frequently sexually and physically abused by others.

Adolescents in detention facilities have higher rates of risky sexual and substance use behaviors than do other adolescents. Adolescents in detention facilities may represent "core" transmitters of STDs since they have problems, such as high rates of drug and alcohol use and poor access to health care, that place them at continuing risk for STDs. Compared to other adolescents, those in detention facilities tend to have engaged in sexual intercourse earlier and more frequently; have engaged in unsafe sexual practices more often; and have higher rates of STDs. Although condom use is low among adolescents in detention, those who communicate with their partners regarding their sexual history and who know someone with AIDS are more likely to use condoms.

Both male and female adolescents in detention facilities have high rates of STDs. A 1994 national survey of state and local juvenile detention facilities found that the rate of gonorrhea was, respectively, 152 and 42 times greater among confined male and female adolescents than among their counterparts in the general population.

Sexuality and Secrecy as a Contributing Factor

Many of the obstacles to prevention of STDs at both individual and population levels are directly or indirectly attributable to the social stigma associated with STDs. It is notable that although there are consumer-based political lobbies and support groups for almost every disease and health problem, there are few individuals who are willing to admit publicly to having an STD. STDs are stigmatized because they are transmitted through sexual behaviors. Although sex and sexuality pervade many aspects of our culture, and sexuality is a normal aspect of human functioning, sexual behavior is a private and secret matter in the United States and also in Nigeria.

Perhaps more than any other aspect of life, sexuality reflects and integrates biological, psychological, and cultural factors that must be considered when delivering effective health services and information to individuals. Sexuality is an integral part of how people define themselves. It influences how, with whom, and with what level of safety people engage in sexual behaviors. However, sexuality is a value-laden subject that makes people including health care professionals, researchers, educators, and the public feel anxious and uncomfortable talking about it. Sexuality has been described in many ways. The common denominator in all definitions is the recognition that sexuality is an intrinsic part of one's being. It is much more than the sexual act and encompasses more than the anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of the sexual response system. It is the quality of being human all that we are as men and women. Sexuality is also energy, a life force, which is an important aspect of individual behavior and includes personal roles, identity, thoughts, feelings and emotions, and relationships. In addition, sex is entwined with ethical, spiritual, and moral issues and is influenced by sociocultural values and norms, religion, family, and economic status.

3.0 Governance and Funding of Sexual health/STIs

Ensuring the continuous availability of high-quality assured sexual health services for all categories of patients/clients could be highly challenging. This may be attributable to the variation in standards and practices within localities, units and/or among staff of the same or different disciplines. The essence of clinical governance is to provide a harmonized and co-ordinated approach that will ensure equality through a combination of both clinical and organizational improvements for better quality healthcare services. In recent years there have been notable achievements in advancing the sexually transmitted infection response. Despite the relative high prevalence of some STIs, global efforts have resulted for instance in to an appreciable decline in the incidence of Haemophilus ducreyi (chancroid), syphilis (in general population), and in some post infectious sequelae of such infections e.g. neonatal conjunctivitis. The feasibility of combined approach in dual elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis is now explored with increased number of pregnant women being screened and better access to adequate treatment. Additionally, improved access to human papillomavirus vaccination appears to be promising in efforts to reduce cervical pre-malignant lesions and genital warts. Acceleration of the global response through clinical governance will ensure progress and sustainability of the current achievements while triggering more successes in the prevention/control and management of STIs.

Healthcare Governance has been defined as “a wide range of steering and rule-making related functions carried out by governments/decisions makers as they seek to achieve national health policy objectives that are conducive to universal health coverage”.(10) Clinical governance which has also been used in this context is said to encompass all the systems and processes which are needed to ensure that providers of clinical and related services are able to deliver safe, high quality and cost-effective care.(11) Established protocols/guidelines specific to STIs are available in most developed nations. However, developing nations like Nigeria have virtually none or non-functional/outdated guidelines. This has made it close to impossible for a uniform and all-encompassing approach to the governance of managing STIs in Nigeria.

Some of the documents from developed nations which holistically addressed sexual health services include “Integrated Sexual Health Services: A suggested national service specification” which was targeted at commissioners and providers of sexual health services in England.(12) It provides patients with an open access to confidential and non-judgmental services including STIs. Mandate was given to local authorities to commission comprehensive open access sexual health services which include free testing and treatment of STIs and notification of sexual partners of infected persons. However even with such documents, discussions and Doctor/Patient relationship on sexual health has remained a major challenge in the management of STI.(13)

The existence of legal frame works regulating the practice of venereology in developed The Venereal Diseases Act was enacted in the UK on the 24th of May 1917 mainly to prevent the treatment of Venereal Diseases by quacks.(14)

Currently in Nigeria, the recommendation by the Federal Ministry of Health on the use of syndromic STI guideline at all levels of care could be misleading and clearly against well established guidelines especially in the context of tertiary healthcare. Syndromic approach to the management of STIs was conceptualized to aid developing nations fight the menace in areas with no laboratory support.

Unfortunately, this approach has further worsened the trend of antimicrobial resistance against common STI pathogens. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is evolving into a superbug with resistance to previously and currently recommended antimicrobials for treatment of gonorrhea, which is a major public health concern globally. Given the global nature of gonorrhea, the high rate of usage of antimicrobials, suboptimal control and monitoring of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and treatment failures, slow update of treatment guidelines in most geographical settings, and the extraordinary capacity of the gonococci to develop and retain AMR, it is likely that the global problem of gonococcal AMR will worsen in the foreseeable future and that the severe complications of gonorrhea will emerge as a silent epidemic.

However, internationally, there is now a high prevalence of N. gonorrhoeae strains with resistance to most antimicrobials previously and currently widely available for treatment (e.g., sulfonamides, penicillins, earlier cephalosporins, tetracyclines, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones). The recent occurrence of failures to treat gonorrhea with the extended-spectrum Cephalosporins (ESCs) Cefixime and Ceftriaxone and the emergence of gonococcal strains exhibiting high-level clinical resistance to all ESCs, combined with resistance to nearly all other available therapeutic antimicrobials, have caused great concern, as evidenced by publications in the medical literature5 An era of untreatable gonorrhea may be approaching.

Overall, strengthening the capacity of health systems will ensure effective service delivery. Health systems, in this context could be “broadly defined as comprising all the organizations, institutions and resources devoted to producing health actions, are a prerequisite to the establishment, delivery and monitoring of programmes on sexually transmitted diseases and the success of their outcomes”.(6) This is an all-encompassing approach that is based on systems thinking in addressing the menace of STIs. In course of strengthening the health systems, importance should be placed on financing to ensure sustainability via resource mobilization, pooling, allocation and payment. In order to ensure quality and equity, stewardship and regulatory guardianship should also be made a priority while applying the concept of public–private partnerships could broaden the impact of the programme to ensure the largest possible coverage.

There is need for national guidelines for case management of sexually transmitted infections. This should be adopted whenever and wherever possible in addition to syndromic management guideline which could be used in primary healthcare setting or where case management is not practicable.

Between September 2002 and March 2006, the WHO developed the Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections 2006–2015 with one of its objectives being “to promote mobilization of funds and reallocation of resources, taking into account national prioritized results-oriented interventions that ensure aid effectiveness, ownership, harmonization, results and accountability.”(6)

The current efforts and strategies towards ending the hidden epidemic of STIs will be critical to the achievement of universal health coverage which is one of the key health targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) identified in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; goal 3. One of such efforts/strategies is the WHO’s global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021 whose vision is to ensure “Zero new infections, zero sexually transmitted infection-related complications and deaths, and zero discrimination in a world where everybody has free and easy access to sexually transmitted infection prevention and treatment services, resulting in people able to live long and healthy lives”.(7)

4.0 Challenges of financing/management of STIs in developing nations

Several challenges pose a lot of threats to the optimum financing/management of STIs in developing nations. Many could be attributed to weak or lack of functional health systems while a significant majority can be linked to ignorance, poverty and other socio-cultural beliefs associated with misconceptions, stigmatization and outright rejection of some treatments or interventions. It is a well-known fact some social determinants drive this hidden epidemic and hinder the response to treatments and interventions. Most developing nations, Nigeria inclusive, lack robust funding arrangements that will be friendly, acceptable and sustainable. This major setback hinders the provision of effective and equitable service coverage with resultant barriers to care and understanding of the needs of women, adolescents and specific population groups.

Although a global problem, the lack of point of care diagnostics for STI is more pronounced in low income countries due to over dependence on syndromic based care. Additionally, in most developing nations, the absence of functional national STIs surveillance has continued to be a major hindrance to adequate data collection for planning on treatment, prevention and control of STIs. This may not be unconnected with lack of unified model for clinics and hospitals that manage STIs while several others do not have any structure in place to cater for this hidden epidemic.

5.0 Healthcare insurance as a model for clinical governance in managing STIs

This should span the entire spectrum of care from preventing, diagnosing, treating and curing of STIs. For any structure to fully succeed, it must be all encompassing with emphasis on women, men, adolescents, men who have sex with men, sex workers, and transgender individuals. This naturally must also take in to cognizance the socio-cultural and religious backgrounds in different parts of the world. Several of the global efforts have attempted to address such problems with varying degrees of success at different levels in different parts of the world. Nigeria has a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) which was established under Act 35 of 1999 Constitution with the following objectives and scope of coverage:(15)

- To ensure that every Nigerian has access to good health care services.

- To protect families from the financial hardship of huge medical bills.

- To limit the rise in the cost of health care services.

- To ensure equitable distribution of health care costs among different income groups.

- To maintain high standards of health care delivery services within the Scheme.

- To ensure efficiency in health care services.

- To improve and harness private sector participation in the provision of health care services.

- To ensure equitable distribution of health facilities within the Federation.

- To ensure appropriate patronage of all levels of health care.

- To ensure the availability of funds to the health sector for improved services.

SCOPE OF COVERAGE:

The contributions paid cover healthcare benefits for the employee, a spouse and four (4) biological children below the age of 18 years. More dependants or a child above the age of 18 would be covered on the payment of additional contributions from the principal beneficiary. However, children above 18 years who are in tertiary institution will be covered under Tertiary Insurance Scheme.

- Out-patient care, including necessary consumables;

- Prescribed drugs, pharmaceutical care and diagnostic tests as contained in the National

Essential Drugs List and Diagnostic Test Lists;

- Maternity care for up to four (4) live births for every insured contributor/couple in the Formal Sector programme;

- Preventive care, including immunization, as it applies in the National Programme on Immunization, health education, family planning, antenatal and post-natal care;

- Consultation with specialists, such as physicians, pediatricians, obstetricians, gynaecologists, general surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons, ENT surgeons, dental surgeons, radiologists, psychiatrists, ophthalmologists, physiotherapists, etc.;

- Hospital care in a standard ward for a stay limited to cumulative 15 days per year.

Thereafter, the beneficiary and/or the employer pays. However the primary provider shall pay per diem for bed space for a total 15 days cumulative per year.

- Eye examination and care, excluding the provision of spectacles and contact lenses;

- A range of prostheses (limited to artificial limbs produced in Nigeria); and

- Preventive dental care and pain relief (including consultation, dental health education, amalgam filling, and simple extraction).

A need for referral

A patient may be referred from a Primary to a Secondary Service Provider due to need for specialized investigations, for medical/surgical reasons or other services such as diagnostic, physiotherapy etc, or referred from secondary to tertiary level.

Approval by the HMOs is necessary, except in emergencies where he cannot be reached and notification of such should be served within 48hours.Referrals ideally should be to the nearest specialist as contained in the list of NHIS registered providers in the area.

The overall aim of the scheme is provision of easy access to healthcare for all Nigerians at an affordable cost through various prepayment systems. Although the objectives and scope of coverage of the scheme have not singled out STIs, most issues to do with their management could be broadly addressed. The greatest challenge is the fact that only about 5% of Nigerians are currently covered by the scheme. Even those covered have their majority being in the formal sector with most of the poor and low socioeconomic populace only relying on out of pocket financing of their healthcare.

6.0 Cost effectiveness of prevention and control of STIs

The benefits of prevention and control of STIs will be tapped at different levels ranging from prevention of STIs transmission/acquisition, early diagnosis and linkage to treatment including that offered to sex partners and asymptomatic patients. Tackling STIs at each of the levels is more cost effective than dealing with complications and sequelae of the infections. To ensure maximum impact there is also the need to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of syphilis/HIV, optimum utilization of HPV/hepatitis B vaccines and controlling the spread/impact of gonococcal antimicrobial resistance.

7.0 Conclusion

The menace of STIs has remained one of the most important public health threats of man from antiquity. The link to socio-cultural and religious life style of man has led to the need for multiple approaches to management due to its complexity. Immunosuppressive conditions including infections such as HIV has changed the epidemiological patterns of STIs. Biological factors, including the lack of signs and symptoms in infected persons, the long lag time from initial infection until signs of severe complications, and the propensity for STDs to more easily infect women than men, contribute to the general lack of awareness of STDs among health professionals and the public. Poverty and inadequate access to health care, substance use, and sexual abuse all increase an individual's risk for STDs. Lack of health insurance is particularly acute among the age and ethnic groups at greatest risk of STDs. Even for the insured, access to comprehensive STD-related services may be difficult. Sex workers, persons in detention facilities, the homeless, migrant workers, and other disenfranchised persons represent "core" transmitters of STDs in the population. Efforts to prevent STDs in the entire community are not likely to be successful unless these groups receive appropriate STD-related services.

All these factors have contributed to the resurgence of STIs and the global challenge of this hidden epidemic thus requiring robust healthcare governance for an efficient and lasting control of STI.

8.0 Future prospects/recommendations about STIs at local and global level

The advent of HIV/AIDs and global threat of growing antimicrobial resistance to common sexually transmitted pathogens such Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Treponema pallidum will be a major challenge to be confronted with by all stake holders in the management of STIs.

Diagnostic capacity at the global level may continue to receive a boost as several ongoing research works are geared towards developing more tools that will address this challenge.

Vaccines such as those against HPV which have played significant role in reducing the disease burden in many developed countries may continue to take centre stage as their use will be expanded and many others might be discovered.

Although there are many global efforts at harmonizing the approach to management and control of STIs, implementation at various levels in different parts of the world especially the resource poor countries are not optimum. There is need for a more general approach that will address the problems at all levels while taking into cognizance the epidemiological, geographical and economic differences between and within countries of the world.

There is an urgent need to scale-up effective STI services including; STI case management and counseling, syphilis testing and treatment, particularly for pregnant women. There is need for promoting strategies for development of global, regional, and national action/response to integrate STI services into existing health systems. Surveillance systems need to be put in place to promote sexual health, measure the burden of STIs and also monitor and respond to STI antimicrobial resistance. Current trend should include the development of novel technologies for STI prevention such as: point-of-care diagnostic tests for STIs, new therapy and vaccines for STIs. Adequate funding should be provided for establishment of functional STI clinics in all Teaching Hospitals. A proposal for establishment of a reference centre for STIs is currently under consideration. Lastly there is need for Government to provide coverage for STI under the National Health Insurance Scheme.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, my unquantifiable gratitude goes to Almighty Allah, my creator and my main source of inspiration. To Him be all the glory, honour and adoration for His mercies upon me and my family. I am grateful to my teachers, too numerous to mention over the past four decades. I must specifically mention Prof Abimbola Olu Osoba, a teacher of teachers and a great lover of STI, my mentor and a great source of inspiration to me. May his gentle soul continue to rest in peace.

My acquaintance with eminent Microbiologists like Prof Tolu Odugbemi, Prof Boaz Adegboro has made a better person out of me. Indeed, I have been able to stand tall by leaning on the shoulders of giants in my Profession.

I also wish to acknowledge the support of two of my mentees Dr. Abike Fowotade and Dr. Mohammed Manga who have been very supportive and contributed significantly towards the success of this lecture. Their enthusiasm and keen interest made the preparation of this lecture an easy one for me.

I owe a huge debt of thanks to Dr. Tony Onipede for painstakingly reading through the lecture and offering useful suggestions. I am indeed very grateful.

Finally, I thank the faculty of Laboratory medicine that nominated me and the West African College of Physicians (Nigerian Chapter) for the acceptance of the nomination. I thank you all for being here today to honour me. May the Lord honour and bless you all. Amen

REFERENCES

- G B. History of sexually transmitted infections (STI). - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23007208

- STID? The Case for a New Term [Internet]. American Sexual Health Association. [cited 2019 Feb 24]. Available from: http://www.ashasexualhealth.org/stid-the-case-for-a-new-term

- WHO | Defining sexual health [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2019 Feb 24]. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/

- Public Health England and Department of Health and Social Care/Healthy Behaviours/10800. Integrated Sexual Health Services: A suggested national service specification. Crown copyright; 2018.

- 5. Satcher D, Hook EW, Coleman E. Sexual Health in America: Improving Patient Care and Public Health. JAMA. 2015 Aug 25;314(8):765–6.

- 6. Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/2019/GBD_2017_Booklet.pdf

- 7. Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S, Field N, Soldan K, Tanton C, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). The Lancet. 2013 Nov 30;382(9907):1795–806.

- 8. Global estimates of prevalent and incident Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS ONE 9(12): e114989.

- 9. O'Leary D. The syndemic of AIDS and STDS among MSM. Linacre Q. 2014 Feb;81(1):12-37. doi: 10.1179/2050854913Y.0000000015. PubMed PMID: 24899736; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4034619.

- 10. Ogunbanjo BO. Sexually transmitted diseases in Nigeria. A review of the present situation. West Afr J Med. 1989 Mar;8(1):42–9.

- 11. Fish AN, Fairweather DV, Oriel JD, Ridgeway GL. Chlamydial trachomatis infection in a gynecology clinic population: identification of high-risk groups and the value of contact tracing. Eur J ObstetGynecolReprodBiol1989;31:67-74.

- 12. Cates W Jr. Epidemiology and control of sexually transmitted diseases in adolescents. In: Schydlower M, Shafer MA, eds. AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. Philadelphia: Hanly&Belfus, Inc., 1990:409-27.

- 13. Moses S, Bradley J, Nagelkerke N, Ronald A, Ndinya-Achola J, Plummer F. Geographical patterns of male circumcision practices in Africa: association with HIV prevalence, Int J Epidemiol , 1990, vol. 19 (pg. 693-7).

- Kreiss JK, Hopkins SG. The association between circumcision status and HIV infection among homosexual men. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1993;168:1404–1408.

- Aral SO, Holmes KK. Epidemiology of sexual behavior and sexually transmitted diseases. In: Holmes KK, editor; ,Må PA, editor; , Sparling PF, editor; , Weisner PJ, editor; , Cates W Jr., editor; , Lemon SM, editor. , et al., eds. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1990:19-36.

- 16. Scholes D, Stergachis A, Ichikawa LE, et al. Vaginal douching as a risk factor for cervical Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:993–7.

- Wolner-Hanssen P, Eschenbach DA, Paavonen J, et al. Association between vaginal douching and acute pelvic inflammatory disease. JAMA. 1990;263:1936–41.

- Critchlow CW, Wolner-Hanssen P, Eschenbach DA, Kiviat NB, Koutsky LA, Stevens CE, et al. Determinants of cervical ectopia and of cervicitis: age, oral contraception, specific cervical infection, smoking, and douching. Am J ObstetGynecol1995;173:534-43.

- Joshua Kimani, Ian W. Maclean, Job J. Bwayo, Kelly MacDonald, Julius Oyugi, Gregory M. Maitha, Rosanna W. Peeling, Mary Cheang, Nicolaas J. D. Nagelkerke, Francis A. Plummer, Robert C. Brunham, Risk Factors for Chlamydia trachomatis Pelvic Inflammatory Disease among Sex Workers in Nairobi, Kenya, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 173, Issue 6, June 1996, Pages 1437–1444, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/173.6.1437.

- Mostad SB, Overbaugh J, DeVange DM, et al. Hormonal contraception, vitamin A deficiency, and other risk factors for shedding of HIV-1 infected cells from the cervix and vagina. Lancet. 1997;350:922–7.

- Koelle DM, Benedetti J, Langenberg A, Corey L. Asymptomatic reactivation of herpes simplex virus in women after the first episode of genital herpes. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:433–8.

- Freeman, H. E., Blendon, R. J., Aiken, L. H., Subman, S., Mullinix, C. F., Et al. 1987. Americans report on their access to health care. Health Aff. Spring: 6-1 8

- Freeman HE, Corey CR. Insurance status and access to health services among poor persons. Health Serv Res. 1993 Dec;28(5):531-41. PubMed PMID: 8270419; PubMed.

- UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, unpublished data, 1996.

- Greenberg MSZ, Singh T, Htoo M, Schultz S. The association between congenital syphilis and cocaine/crack use in New York City: a case-control study. Am J Public Health 1991;81:1316-8.

- Marx R, Aral SO, Rolfs RT, Sterk CE, Kahn JG. Crack, sex, and STD. Sex Transm Dis 1991;18:92-101.

- U.S. Department of Justice. Selected findings: violence between intimates, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ-149259. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, 1994.

- Guidry HM. Childhood sexual abuse: role of the family physician. Am Fam Physician 1995;51:407-14.

- Miller BC, Monson BH, Norton MC. The effects of forced sexual intercourse on white female adolescents. Child Abuse Negl1995;19:1289-301.

- Gutman LT, St. Claire K, Herman Giddens ME. Prevalence of sexual abuse in children with genital warts [letter; comment]. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1991;10:342-3.

- CDC. 1993 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR 1993;42(No. RR-14):56-66.

- AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics), Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Guidelines for the evaluation of sexual abuse of children. Pediatrics 1991;87:254-60.

- Donovan P. Taking family planning services to hard-to-reach populations. Fam PlannPerspect1996;28:120-6.

- Thomas JC, Tucker MJ. The development and use of the concept of a sexually transmitted disease core. J Infect Dis 1996;174(Suppl 2):S134-43.

- Plummer FA, Ngugi EN. Prostitutes and their clients in the epidemiology and control of sexually transmitted diseases. In: Holmes KK, editor; , March P-A, editor; , Sparling, editor; , PF, editor; , Wiesner PJ, editor; , Cates W Jr., editor; , Lemon SM, editor. , et al., eds. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1990:71-6.

- Darrow WW. Assessing targeted AIDS prevention in male and female prostitutes and their clients. In: Paccaud F, editor; , Vader JP, editor; , Gutzwiller F, editor. , eds. Assessing AIDS prevention. Basel, Switzerland: BirkhäuserVerlag, 1992:215-31.

- Rosenblum L, Darrow W, Witte J, Cohen J, French J, Gill PS, et al. Sexual practices in the transmission of hepatitis B virus and prevalence of hepatitis delta virus infection in female prostitutes in the United States. JAMA 1992;267:2477-81.

- Bakare, R.A.,Oni,A.A., Umar, U.S., Adewole, I.F., Shokunbi, W.A., Fayemiwo, .A., Fasina, N.A.(2002) Pattern of Sexually transmitted diseases among Commercial sex workers (CSWs) in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afri. J. Med. med. Sci.31: 243-246.

- Bakare, R.A., Oni, A.A., Umar, U.S., Fayemiwo, S.A., Fasina, N.A., Adewole, I,F., Shokunbi, W.A. (2002): Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis among Commercial sex workers (CSWs) in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afri. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 3(2): 72.

- Dada, A. J., A. O. Ajayi, L. Diamondstone, T. C. Quinn, W. A. Blattner, and R. J. Biggar. 1998. A serosurvey of Haemophilusducreyi, syphilis, and herpes simplex virus type 2 and their association with human immunodeficiency virus among female sex workers in Lagos, Nigeria. Sexually Transmitted Diseases; 25: 237-242

- Bakare, R.A., Oni, A.A, Umar, U.S, Okesola, A.O, Kehinde A.O, Fayemiwo, S.A. (2003). Sero-prevalence of HIV infection among commercial sex workers (CSWs) in Ibadan, Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetric &Gynaecology. 20 (1): 12-15

- Caceres, C.F., van Griensven, G.J. (1994). Male homosexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDS 8: 1051-1051.

BIODATA OF PROFESSOR RASHEED AJANI BAKARE

Professor Rasheed Ajani Bakare was born 5th February 1953 in Kemta, Abeokuta South Local Government, Ogun State. He had his primary education at Ahmadiyya primary school, Abeokuta between 1960 and 1965. Thereafter, he attended Abeokuta Grammar school between 1968 and 1972 for his secondary education where he further obtained his Higher school certificate (HSC) education in the year, 1974.He then proceeded to the prestigious University of Ibadan, where he obtained a MB; BS degree in July,1981.

He had his internship at the University College Hospital, Ibadan in 1981/1982 and National Youth Service Corps at Ikire between 1982 and 1983. He started his residency training at the University College Hospital, Ibadan in August, 1983. He became a Fellow of the Nigerian Postgraduate Medical College (Pathology) in the year 1990 and a Fellow of the West African College of Physician (Laboratory Medicine) in 1995. Professor Bakare specialized in Clinical Bacteriology and Venereology and has been a Consultant Clinical Microbiologist/Venereologist and Professor of Clinical Microbiology in the Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Nigeria

He was appointed Lecturer 1 on the first of January, 1991 and Honorary Consultant to the University College Hospital the same day. He was promoted senior lecturer in October, 1996. He obtained his Chair in the Department of Medical Microbiology in October, 2002.

He was appointed Clinical Head of Department of Medical Microbiology in the years 1994 to 1997 and was also acting Head of Department for several years. He became the substantive Head of Department from 2004 to 2011. He was Principal Investigator for Ibadan SAVVY project (A multicentre Microbicide trial sponsored by USAID and monitored by FHI North Carolina, USA) between 2004 and 2007. He is currently a member of African Collaborative Center for Microbiome and Genomics Research (ACCME) Research Group (part of the H3Africa Consortium) as co-PI.

He is a recipient of several Grants and has also enjoyed several International Travel Fellowship from several Multinational Drug Companies.

He has been and still remains External examiner to many Medical Schools in Nigeria. He has also been involved in supervision and examination of Postgraduate students including Resident doctors and PhD candidates.

He was appointed by the FMOH as the Chairman of the Technical Working group for Sexually Transmitted Infections in Nigeria. Prior to these he has been a member of the group since 1996. He has also participated in Accreditation programme in Laboratory Medicine both within and outside the Country.

His honors, distinctions and memberships of learned professional bodies include the Nigerian Medical Association, He has also been the President of the Nigerian Venereal Disease Association (NIVEDA now IUSTI) between 1997 and 2007. He received Recognition of service award from the University College Hospital, Ibadan after his tenure as Deputy Chairman, MAC (Laboratory services) from 2007 to 2011. He is a 1 star Paul Harris Fellow and also a recipient of several recognition awards from the Rotary International.

Professor RA Bakare is a Venereologist of high repute and has made significant contribution to the field of Venereology in Nigeria. He is the Director of the Special Treatment Clinic and Venereal Diseases and Treponematoses Research and Teaching Laboratories (A WHO Collaborating Center and a Reference laboratory for STDs in Nigeria) from 1990 till date. A widely traveled man, attending both local and international conferences and workshops, he has published more than 100 journal articles in both local and international journals. He is the Editor-in-Chief of the Nigerian Journal of Genitourinary Medicine. He is happily married and blessed with four wonderful children.